https://www.inkandswitch.com/potluck/

Highlights

-

We’ve found that starting with freeform documents promotes a wide variety of use cases. Existing notes can serve as inspiration, rather than trying to build applications from a blank slate. We’ve also found that barebones text-based UIs are sufficient for many personal use cases, without the need for a full layout design.

-

One problem with apps is that they have predefined feature sets that the creators deemed appropriate for the goal. It’s impossible to make a small tweak, or even remove an unwanted feature, unless the creator of the app has explicitly allowed for the change. Each app has a (often narrow) domain that it considers in scope, requiring us to learn to use many independent apps that don’t compose together well. In short, apps enact rigid boundaries between tasks, and define rigid solutions within those boundaries.

-

In the analog world, it’s natural to combine a grocery shopping list with other chores for the day, but there’s no way to easily integrate a Paprika shopping list with other notes in another app.

-

There’s another important dimension of inflexibility: apps create rigid data schemas that define the kinds of information we can record within them. We can fill out the available form fields, but we can’t add new fields or scribble in the margins.

-

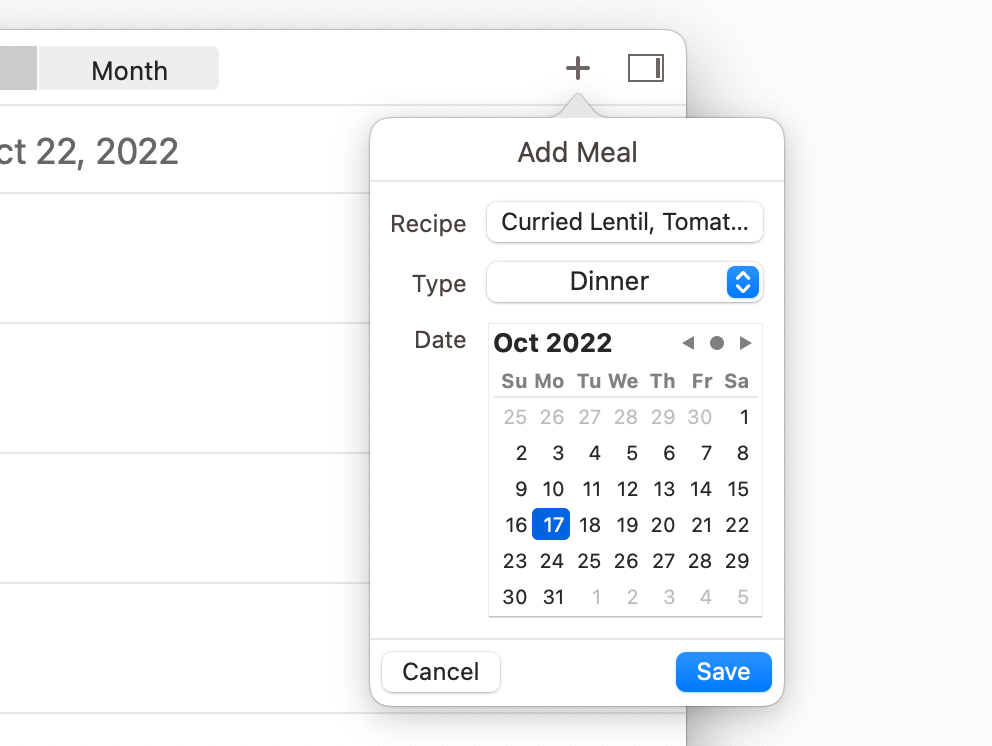

There’s no way to ambiguously assign a recipe to either Tuesday or Wednesday, which would be natural to do in a paper notebook.

Each meal plan entry in Paprika must be assigned to a specific date on the calendar, with no room for ambiguity.

Each meal plan entry in Paprika must be assigned to a specific date on the calendar, with no room for ambiguity. -

1991, in Eric Bier and Ken Pier’s work on Documents as User Interfaces at Xerox PARC. They demonstrated that if we treat specific segments of text as clickable buttons, then we can arrange them in a UI by simply moving the text to the appropriate place in the flow of the document.

-

. These tools share Potluck’s goal of building on top of the familiar and portable format of plain text, and many of them also have robust ecosystems of user-authored plugins which can extend the tools to more domains and tasks. However, these tools also tend to come with some degree of built-in, opinionated syntax and features, and writing plugins often requires leaving the tool and applying expert programming skills.

-

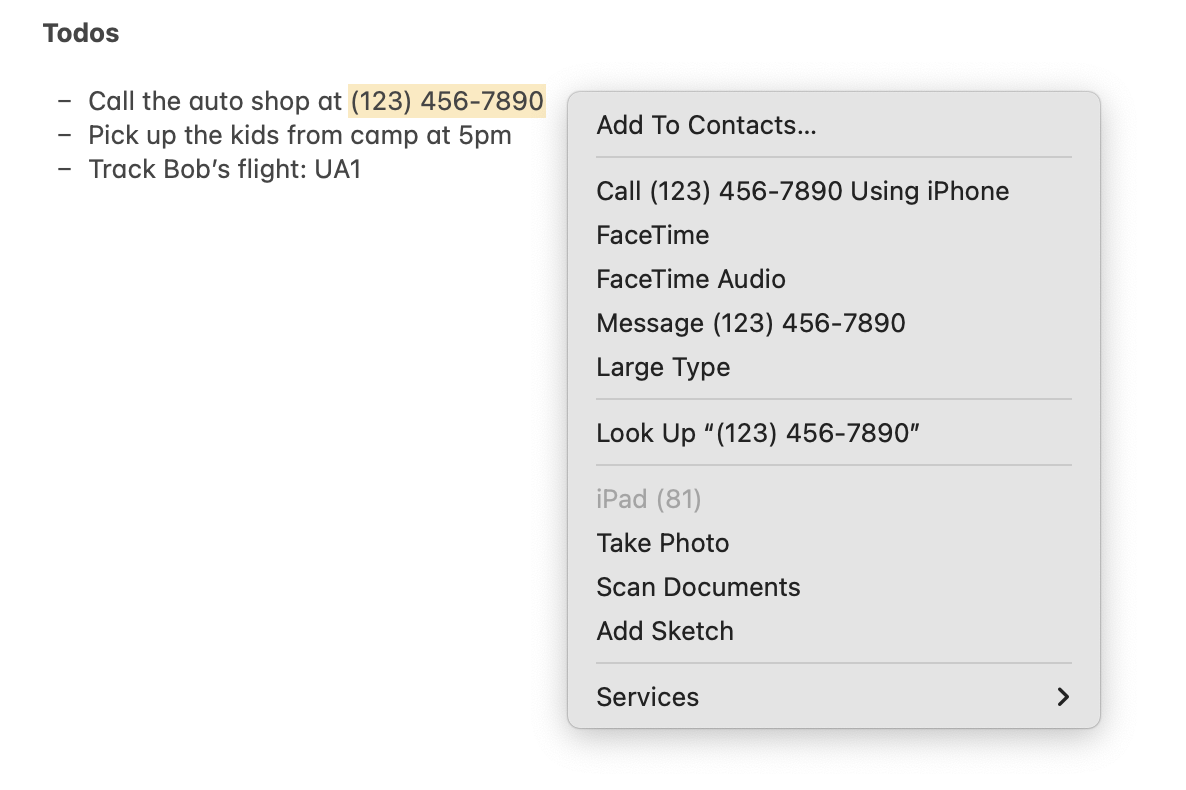

We find data detectors promising because they allow people to represent information on their own terms. However, today data detectors are more of a minor convenience than a core metaphor in the OS. We think the reason is that the interaction model around data detectors is limited: all a user can do is manually click on a detected value and take a single action. There’s no ability to perform more sophisticated computations with the detected data, or to automatically show annotations on detected data.

A data detector in macOS enables right-clicking on a phone number to add it to contacts or make a phone call.

A data detector in macOS enables right-clicking on a phone number to add it to contacts or make a phone call. -

In our experience, these kinds of tools feel nice to use because they strike a good balance between natural language and formal syntax. They allow the user to type naturally, but they don’t aim to accurately interpret everything someone could possibly write. There’s a feedback loop where the user adjusts their input in response to the machine.

-

One category of approaches is to develop better languages. For example, LAPIS, by Rob Miller, developed a set of tools for specifying and extracting patterns from text by composing together existing patterns, including a friendly syntax that resembles natural language. Another route is programming by example (PBE): letting users provide concrete examples to specify a more general pattern.

-

There are also some interesting hybrid interaction models between PBE and code editing—in User Interaction Models for Disambiguation in Programming by Example, Mayer et al. use PBE to generate candidate programs, but also let users directly edit the resulting programs.

-

As an easy start, the user can search for a string literal:

11 g, the quantity of coffee in our recipe. The search result appears in a table in the search panel, and is also underlined in the text note itself. Searches run continuously against the note’s content, so the results update as we update the text note: -

. In Potluck, the user can do this by rewriting their search from

11 gto{number} g. This works because Potluck searches can reference other existing searches, by putting the name of an existing search inside of curly braces.