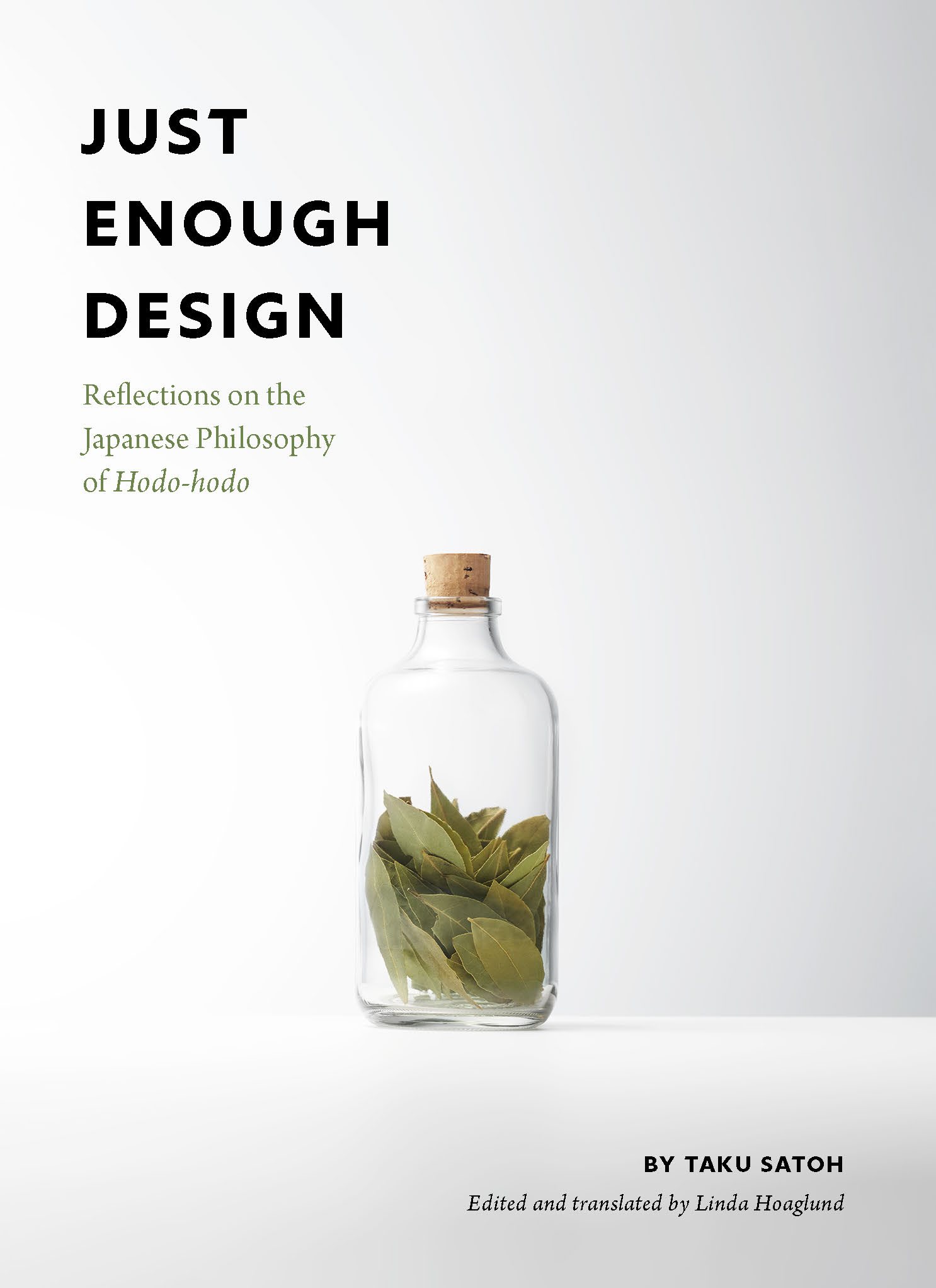

Holding back before completion gives us precisely the room that we need to respond to any object according to our unique sensibilities. You could say that this space is what allows us to customize our relationships with objects. Each individual has a particular set of values and behaviors. Thus, when presented with an object that has no space left, many of us feel walled in, with no room to breathe. When an object feels like it’s taunting us, saying “Use me this way!” or when it is so stunning that no one can imagine how to put it to use, this is because it has no space. Brands and designers often race single-mindedly to perfect something as though it’s a work of art. But design has no inherent value. Its value is only born of the relationship that individuals develop with an object. Given that we each have our own priorities, shouldn’t we hold back design at just enough, leaving room to accommodate a range of interactions? This is how space is created.

Mako Fujimura’s idea of stopping a work “when it is most pregnant” echoes this — design that holds back before completion leaves room for the user to complete the relationship. When enterprise requirements drive product design to exhaustive specificity, the craft suffers. Leaving intentional space allows organizations and individuals to customize their own interaction with the object. craft