WE’RE NOT MEANT to see or know everything about everyone, not even our closest friends. Paradise is lost when we eat from the Tree of Knowledge.

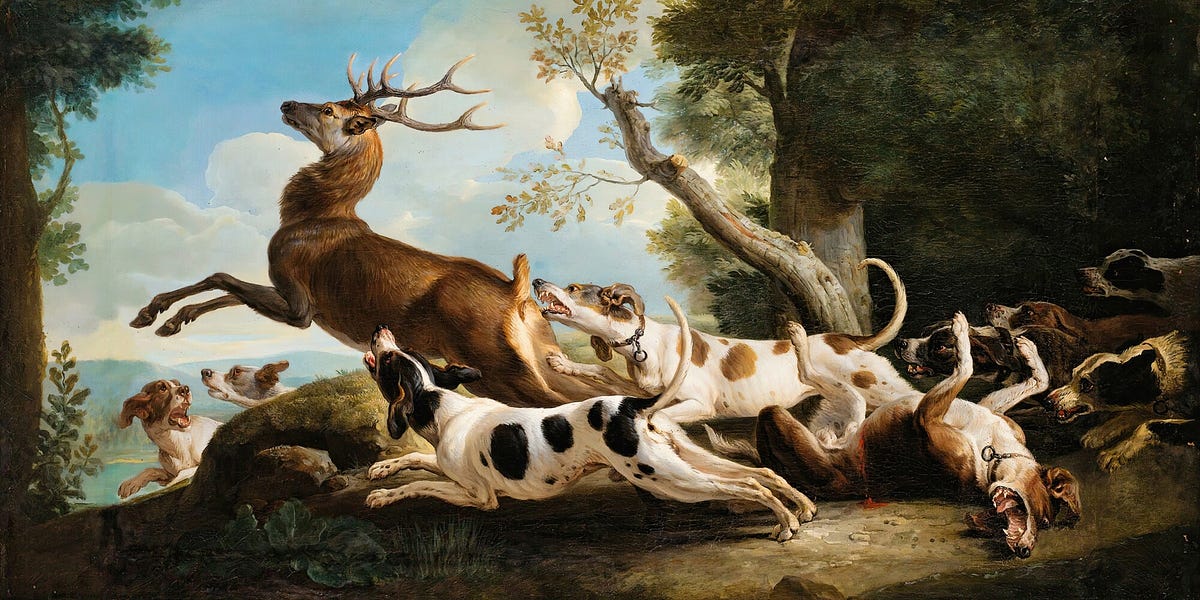

She had taken the very story of himself, the myth in which he played the proud victor, the poor victim, or anything more than a stag with a cry in its throat and dogs in its wake. And when the dogs found him, they did what they were trained to do, and when they were done, they sat in a ring around the shredded thing that had once been their master. Eyes blank, they waited—because they didn’t understand why the horns had not sounded or why the man did not appear. The story ends here. While Artemis is no exhibitionist, the message is clear: Not everything can be looked at and leave you as whole as you were before. Seeing too much can shred you into pieces. A showy culture without privacy loses the ability to contemplate. Our culture of showing corrodes the very art of observing.

Why has it become so difficult to think deeply and thoroughly and appreciate one thing before moving on to the next? As Carl Jung said, “Thinking is difficult, that’s why most people judge.”

Thinking operates through naming and creating rather than judging. Knowing a place relationally — attending to what is present in the neighborhood — bears more fruit than pursuing correctness. Judgment forecloses; relational attention opens.“Contemplation” comes from the Latin, contemplatio, which comes from templum—the space marked out for augury, a sacred space reserved for watching the signs of the divine. Templum is also where we get the word “temple”, a consecrated space. With the prefix con-, meaning “with”, contemplation means to be with the temple, or to dwell within the sacred space of attention. Contemplation is much deeper than thinking. It implies a religious observation. It implies intention, slowness, interiority, reverence.

Contemplation’s etymological root in “templum” — sacred space for watching divine signs — positions art-making as midwifery: giving language to what exists at the threshold between known and unknown. The altar brings things to visibility without forcing them fully into the light. The artist’s task is to attend to what is pregnant with possibility without collapsing it into certainty.It implies flashiness and an offensive lack of modesty. A culture that pushes for everything to be in-your-face makes it difficult to identify, let alone respect, the sacred. As a result, the world is thinned to a series of backdrops: landscapes framed for the lens, meals plated for the photograph, sunsets watched only long enough to be posted. Exhibitionism turns places into décor, moments into promotional stills. Human lives are pressed flat into their own reflections

The desire to flatten the world through increased accessibility is a desire for legibility — to characterize and predict where people ought to be rather than to encounter them as they are. Exhibitionism serves categorization, not contemplation.We are not living deliberately or, as Henry David Thoreau said, sucking out all the marrow of life: “I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practise resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms.”

YOU HAVE TO STAND STILL so that the enchantment of the world can step out of its shyness. Contemplation isn’t measured by time or the amount of given information, but by stillness. This is also why contemplation is the process of recognizing beauty.

Meaning emerges from the rearrangement of the world — from seeing patterns and sequences — but recognizing these patterns requires stillness. Beauty is not in the individual elements but in their constellation, and that constellation only becomes visible when attention slows enough to see it.when beauty shows itself, you’ll not only find it sweet but find it as a pulse of unignorable recognition, a sight pulling you toward what is real, toward what lives beyond the reach of cameras and screens and magazines.