struggled with writing for decades. As a student, I wrote prolifically when deadlines threatened to chop my ‘A*’* off, but disciplined writing eluded me. Instead I collected notebooks, carrying one with me everywhere, filled with sentence fragments, to-do lists, and doodles — and I started a good half-dozen projects, none of which lasted two months. I dreamed. A lot.

-

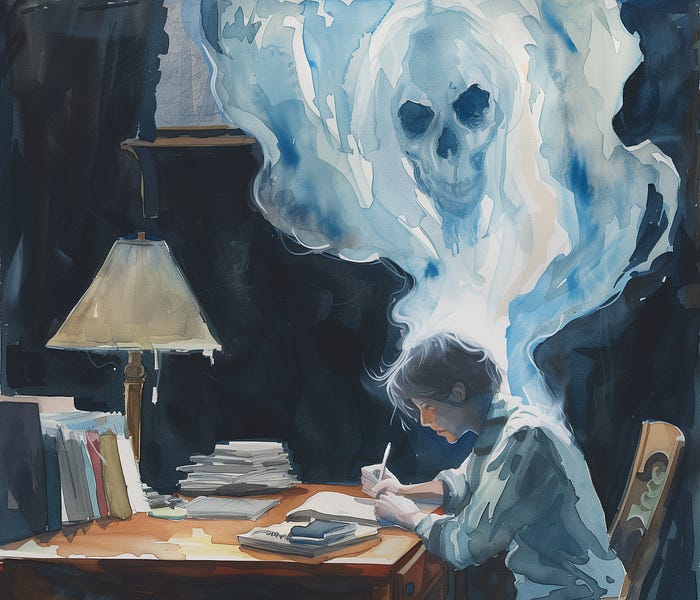

Anxiety intrudes into writing in two ways:

- Complex writing is intrinsically anxiety producing. According to psychology, a main cause of anxiety is goal conflict. Clashing goals create discomfort. Writing is full of clashing goals. When you write you plan, research, compose and edit all at once. These tasks clash, producing a steady stream of high-friction moments and tricky problems. Each conflict is draining, and each conflict produces a desire to leave, forcing you to exert effort just to keep working.

Concern over how our writing will be received also produces anxiety, especially when the audience is important. Picture an email to a colleague and compare it with an email to your boss — one is an afterthought; the second is a struggle. Writing grows much more difficult when the outcome matters. Mixing both types of anxiety gums everything up by adding an extra layer of impression management to the writing process — an impossible layer, since you’re managing

- We form a series of toxic preconditions — misguided beliefs about what writing must be, in order to be “worth it.” I’m going to focus on three here. You can think of them as the non-writer’s preconditions for writing:

- Writing should be worthwhile. Since writing is a high-cost activity we decide it should only be used on high-reward projects.

- Writing should be done once**.** Since writing is a struggle there’s diminishing value to doing anything that isn’t the project.

Writing should be done right. Further, since writing is a struggle, there’s no reason to circle back to edit it and make it better. One and done. Who in their right mind would sign up for a second beating? Most problems I have seen with writing stem from these preconditions. There are methods to make writing much easier,

Atomic notes function as a release valve for the “writing should be done once” precondition — by siloing a thought into a self-contained unit, the writer can treat each note as complete without the pressure of perfecting a larger composition.

Undoing Toxic Precondition

#1 (Writing Should be Worthwhile) The key to overcoming this precondition is recalibrating what you consider worthwhile. An example: Since 2019 I’ve produced over 400,000 words of published text (including 200,000 words for blogging platforms like Medium and Substack). But that’s only about a third of what I’ve written. The rest is invisible. Why? Because it’s dirt. “Dirt” doesn’t mean bad compositions. It means most of my writing is not composition. It’s random thoughts, or notes to myself, or explorations into my interests. My rule is to listen to my brain — if it wants to write nothing but to-do lists for two weeks, I listen to it.write to purge noise when my brain is too loud and to make noise when my brain is too quiet. It’s too mundane to be a journal. But it’s vital to me. Meta-writing helps me think. It helps me hobble along when my brain is full of static, which is often. I have found it to be deeply invaluable in constructing ideas, exploring my soul, and just working through what I am going to do each day.

Praxis. This refers to your knowledge base — the raw material you draw from when writing. Most people build their praxis haphazardly. Their material is kept mainly inside their head and they only add to it when they are researching a term paper. However, if you are committed to writing regularly, one of the most pleasant writing activities you can do is to build your praxis deliberately by researching and writing about your interests. Write to learn.

Multi-pass writing is simpler, more fun, and more sustainable. You can do what works for you, but here are two techniques I use regularly: • Outlining. I used to avoid outlining. Whenever I tried, I wound up deviating from my outline, so it felt like a wasted step. Later, I recognized this is natural. New angles spring from an outline in the same way that new possibilities for artwork spring from a sketch. Even when you deviate, outlining is useful because it releases mental tension. Getting the big-scale composition on paper stops it from interfering with your other writing tasks. Outlining is a classic for a reason; it works. • Write a Splat Draft. Alternatively, you can write your draft in one long, stream-of-thought rant. I call these “splat drafts” — you get everything in your head out on the page at once, without regard for form (hence the “splat”). Then you treat it as the raw material for a second, proper draft. Think of it as the act of dumping the puzzle pieces out on the table so you can sift through them and see what fits together.

What if we designed for the cognitive affordances of how we’d like our relationships with technology to be — in terms of what we can provide ourselves as products for stimulusDeliberate Incorrectness. Having trouble with your internal editor? Here’s a delightful way to get rid of it: Deliberately commit to writing badly. You can do this many ways. One of my professors insisted that his graduate students send their first draft of an academic article to him in an email. You can think of it as a form of strategic un-professionalism. Clive Thompson, a prolific writer, suggests a version of this as well. But you can take it further; if you’re paralyzed by your internal editor, try adopting a persona so ridiculous that you can’t edit it. When I was paralyzed as an undergraduate I would write a “stoner draft” — my goal was to write a draft that sounded like it was dictated into a cell phone by a surf rat hopped up on ganja. There was no way to write an A+ paper in the middle of all the whoa dude and lol righteous, so my internal editor gave up cleaning until later, which was the goal.